CS2107 (AY23/24 Sem 2) Assignment 1 Writeup

I took CS2107 - Introduction to Information Security this semester at school under Prof. Chang Ee-Chien. As a part of this course, I had to solve two CTF assignments.

Here, you’ll find my writeup for the first CTF assignment. This assignment was crypto-heavy as the first half of the semester was spent covering Cryptography (Encryption, Hashing, Authentication).

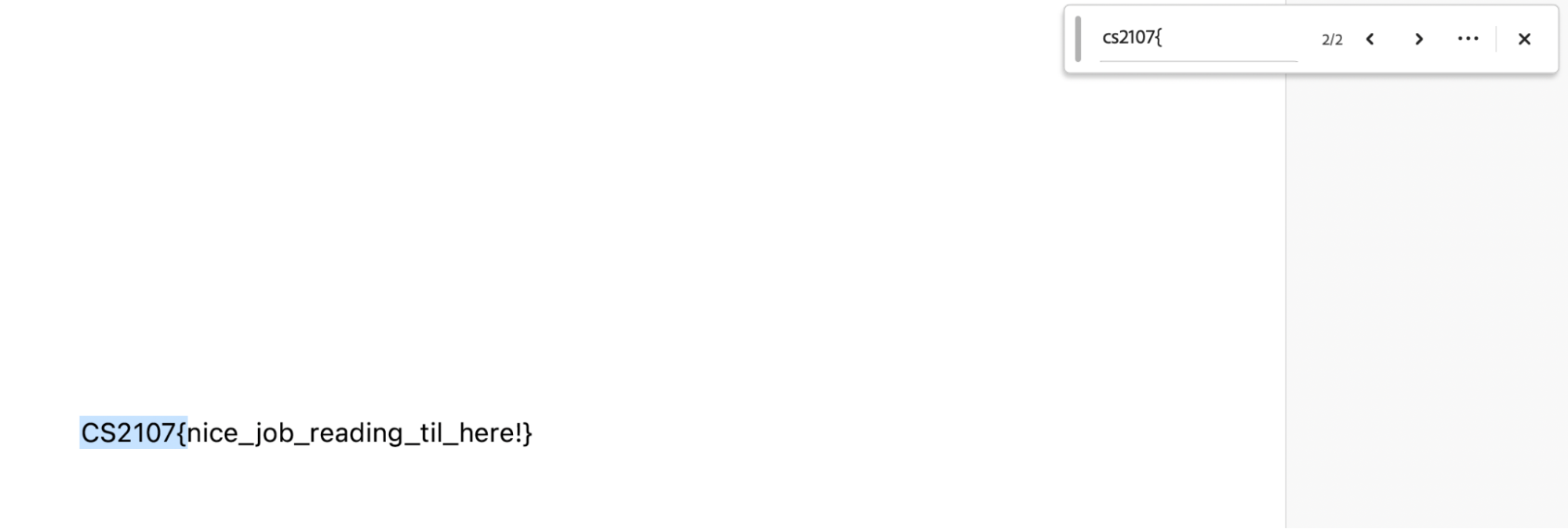

E.0 Sanity Check (0 marks)

A flag, written in our flag format, is placed somewhere in the assignment instruction file.

Try to find and submit it!

Flag format:

CS2107{...}

Open the Assignment 1 PDF with any PDF reader. Then, simply press Ctrl/Cmd + F and type in CS2107{ into the search bar.

The flag is: CS2107{nice_job_reading_til_here!}

E.1 Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (10 marks)

Bob and Alice are good friends who have been sending each other secret messages. Unfortunately, Bob accidentally revealed some sensitive information while transmitting the secret message. Using sniffing techniques, Mallory managed to intercept the message from Bob and now wants to decrypt them. But how?

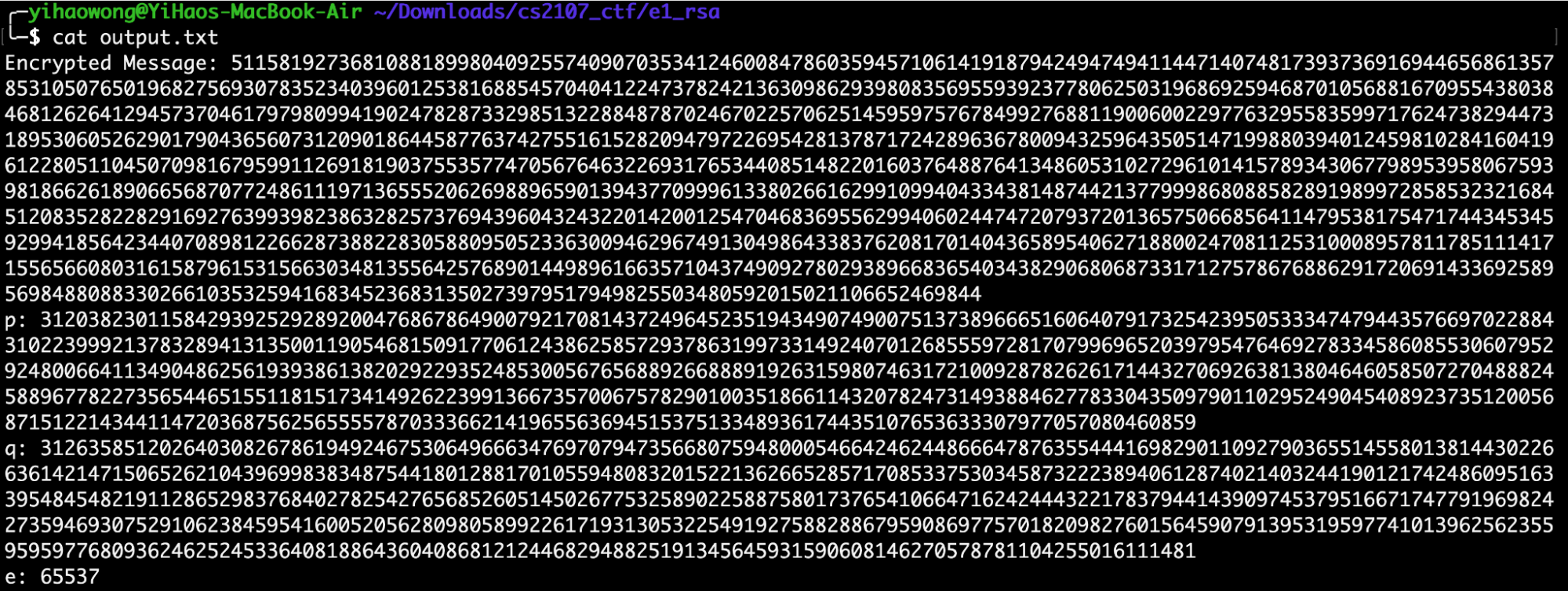

If we view the contents of the output.txt file provided to us, we see the following:

As the challenge title suggests, RSA encryption is involved. It is noted that the values of $p$, $q$ and $e$ are provided, along with the encrypted message. Given this, we can attempt to decrypt the message using RSA.

For RSA, we will also require the following values, $n=pq$ $\phi=(p-1)(q-1)$

both of which can be easily calculated (since $p$ and $q$ are given).

Crucially, for RSA, we also wish to note that this property holds, $de \mod \phi=1$ where $d$ is the decryption key and $e$ is the exponent 65537.

What this property implies, is that $d$ is the modular inverse of $e$. That is, $d=e^{-1} \mod \phi$.

From here, once we have computed $d$, we can simply apply the following formula to decrypt the message: $m=cd \mod n$

We will solve this using a Python script:

import binascii

import pwn

# Set/compute necessary values for RSA decryption

enc_msg = 511581927368108818998040925574090703534124600847860359457106141918794249474941144714074817393736916944656861357853105076501968275693078352340396012538168854570404122473782421363098629398083569559392377806250319686925946870105688167095543803846812626412945737046179798099419024782873329851322884878702467022570625145959757678499276881190060022977632955835997176247382944731895306052629017904365607312090186445877637427551615282094797226954281378717242896367800943259643505147199880394012459810284160419612280511045070981679599112691819037553577470567646322693176534408514822016037648876413486053102729610141578934306779895395806759398186626189066568707724861119713655520626988965901394377099961338026616299109940433438148744213779998680885828919899728585323216845120835282282916927639939823863282573769439604324322014200125470468369556299406024474720793720136575066856411479538175471744345345929941856423440708981226628738822830588095052336300946296749130498643383762081701404365895406271880024708112531000895781178511141715565660803161587961531566303481355642576890144989616635710437490927802938966836540343829068068733171275786768862917206914336925895698488088330266103532594168345236831350273979517949825503480592015021106652469844

p = 31203823011584293925292892004768678649007921708143724964523519434907490075137389666516064079173254239505333474794435766970228843102239992137832894131350011905468150917706124386258572937863199733149240701268555972817079969652039795476469278334586085530607952924800664113490486256193938613820292293524853005676568892668889192631598074631721009287826261714432706926381380464605850727048882458896778227356544651551181517341492622399136673570067578290100351866114320782473149388462778330435097901102952490454089237351200568715122143441147203687562565555787033366214196556369451537513348936174435107653633307977057080460859

q = 31263585120264030826786194924675306496663476970794735668075948000546642462448666478763554441698290110927903655145580138144302266361421471506526210439699838348754418012881701055948083201522136266528571708533753034587322238940612874021403244190121742486095163395484548219112865298376840278254276568526051450267753258902258875801737654106647162424443221783794414390974537951667174779196982427359469307529106238459541600520562809805899226171931305322549192758828867959086977570182098276015645907913953195977410139625623559595977680936246252453364081886436040868121244682948825191345645931590608146270578781104255016111481

e = 65537

phi = (p-1) * (q-1)

n = p * q

d = pow(e, -1, phi)

dec_msg = pow(enc_msg, d, n)

print(binascii.unhexlify(hex(dec_msg)[2:]).decode())

The flag is: CS2107{pl3ase_$3cure_ur_p_q_RS@}

E.2 xor secure (10 marks)

One-time-pad is really strong, so how about four one-time-pad?? This should be four times as strong.

I have encrypted a secret message using four-time-pad, can you obtain that message? The code used and the output of the encryption is given.

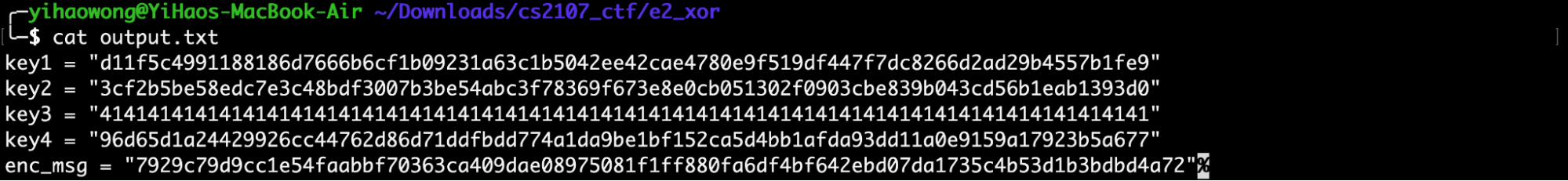

If we view the contents of output.txt, we see the following:

It was mentioned that the original message was encrypted using a “four-time pad”. As 4 different keys are provided to us, we could thus assume that this means the message was encrypted 4 times, using 4 different one-time pads.

Recall that for each encryption using a one-time pad, we XOR our message against a key (which has to be of the same length as the message).

This means that the original message $m$ had underwent this XOR encryption pattern four times, to achieve a “four-time pad”: $m_{enc} =((((m\oplus k1)\oplus k2)\oplus k3)\oplus k4)$

By the associative property of XOR operations, we can also represent the above equation in this manner: $key=k1 \oplus k2 \oplus k3 \oplus k4$ $m_{enc}=m \oplus key$

Crucially, by the nature of XOR operations, we can therefore derive $m$ as follows: $m=m_{enc} \oplus key$

Let’s solve this using a Python script:

import binascii

key1 = "d11f5c4991188186d7666b6cf1b09231a63c1b5042ee42cae4780e9f519df447f7dc8266d2ad29b4557b1fe9"

key2 = "3cf2b5be58edc7e3c48bdf3007b3be54abc3f78369f673e8e0cb051302f0903cbe839b043cd56b1eab1393d0"

key3 = "4141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141414141"

key4 = "96d65d1a24429926cc44762d86d71ddfbdd774a1da9be1bf152ca5d4bb1afda93dd11a0e9159a17923b5a677"

enc_msg = "7929c79d9cc1e54faabbf70363ca409dae08975081f1ff880fa6df4bf642ebd07da1735c4b53d1b3bdbd4a72"

# Convert to bytes

key1 = bytes(binascii.unhexlify(key1))

key2 = bytes(binascii.unhexlify(key2))

key3 = bytes(binascii.unhexlify(key3))

key4 = bytes(binascii.unhexlify(key4))

enc_msg = bytes(binascii.unhexlify(enc_msg))

def xor(msg, key):

return bytes(a ^ b for a, b in zip(msg, key))

combined_key = xor(xor(xor(key1, key2), key3), key4)

msg = xor(combined_key, enc_msg).decode()

print(msg)

The flag is: CS2107{M4St3R_0f_aNc13nT_x0R_t3CHn1qu3s!!!!}

E.3 Hash Browns (10 marks)

Can you “decode” the hashes? Wait it should be one-way right?

Ok your task will be to “decode” these list of hashes.

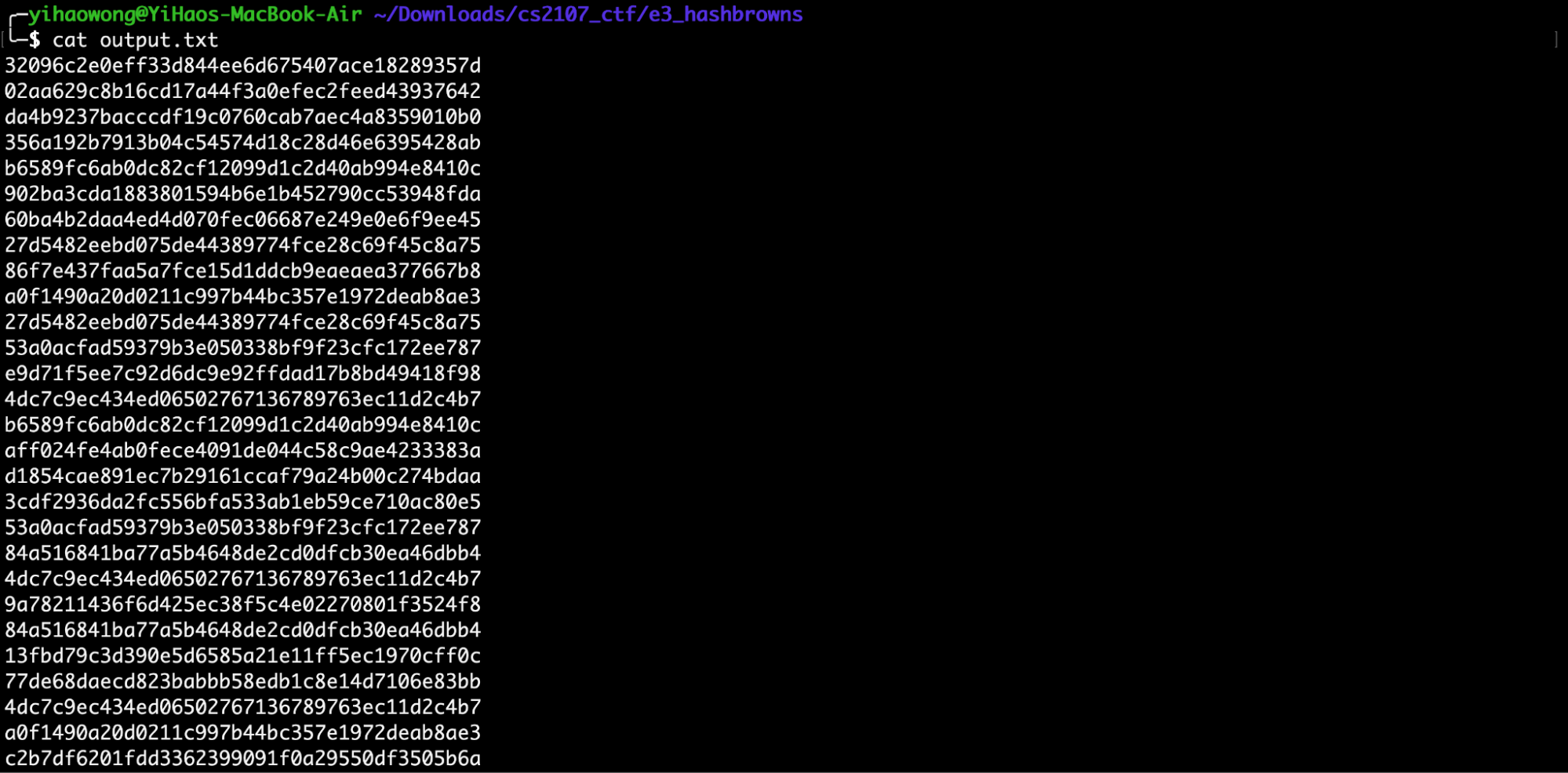

If we view the contents of output.txt, we see the following:

We note that each line of the output contains a 20 byte hex digest. Interestingly, we also note that a few lines, such as 27d5482eebd075de44389774fce28c69f45c8a75 and 53a0acfad59379b3e050338bf9f23cfc172ee787, are actually repeated in the output.

From here, we can assume that the hex digests were generated using a deterministic hash function (due to the presence of repeated digests). Through a quick Google search, we can see that a hash function that generates 20 byte digests would be SHA-1.

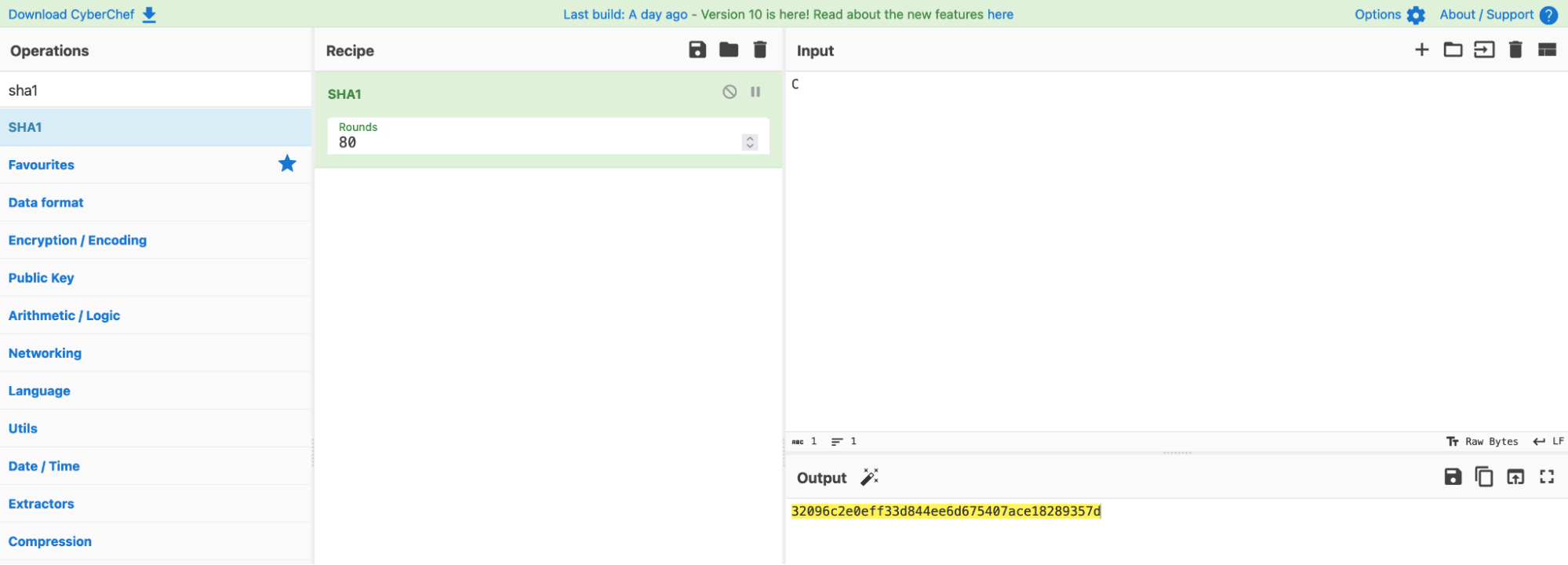

To confirm our suspicions, let’s use CyberChef to check what the SHA-1 hash of ‘C’ is (since we are expecting the output to be a flag in the CS2107{xxx} format, where the first character is ‘C’).

Indeed, we can see that the hash digest matches the first line in the output. We now know that each line of output.txt represents a character in our flag.

Our goal now is to find out the preimage of each hash digest. We can achieve this easily, by firstly, doing an exhaustive search on the SHA-1 hashes for all possible ASCII characters, and mapping each hash digest to its character.

Then, just map each line in the output to its corresponding character.

Let’s write a solver script in Python to determine the value of our flag.

from Crypto.Hash import SHA1

hashmap = {}

for i in range(256):

current_char = chr(i).encode()

current_hash = SHA1.new(current_char).hexdigest()

hashmap[current_hash] = current_char

output = ""

with open('output.txt', 'r') as f:

lines = f.readlines()

for line in lines:

line = line.strip()

output += hashmap[line].decode()

print(output)

The flag is: CS2107{hash_br0wn$_cr@ck3rs}

E.4 Caesar with a capital C (10 marks)

Did you know that Caesar was assassinated with pugiones? Pugiones were actually a type of daggers used by Roman soldiers. There were some doors we found that used daggers as keys, can you help me find my dagger?

This is a caesar cipher challenge. The source code for the encryption is provided. The flag is in the form of

CS2107{flag_text}whereflag_textis replaced by the correctly decoded plaintext.

If we view the contents of caesar.txt, we see the following value of 890d_u890d_q8r5s_0vz88ed, which we can presume to be the resultant ciphertext from a Caesar Cipher.

We can look at caesar.c to determine the shift amount (key) used in this Caesar Cipher.

From caesar.c, we see that the key is:

int key = 16*3-4+3-4/2-40

This key value equates to 5.

We also observe that the cipher was applied on alphabets and numbers. We wish to note that there are 26 alphabet characters and 10 numeric characters, and thus, the sizes of the character sets are different.

To decipher a Caesar Cipher, we will simply need to apply the Caesar Cipher once more, but this time, we will shift our character set by a new shift amount, computed as follows:

new_shift_amount = character_set_size - original_shift_amount

This new shift amount allows us to “reset” back to our original character set.

Thus, for alphabet characters, the new shift amount is $26-5=21$. For numbers, the new shift amount is $10-5=5$.

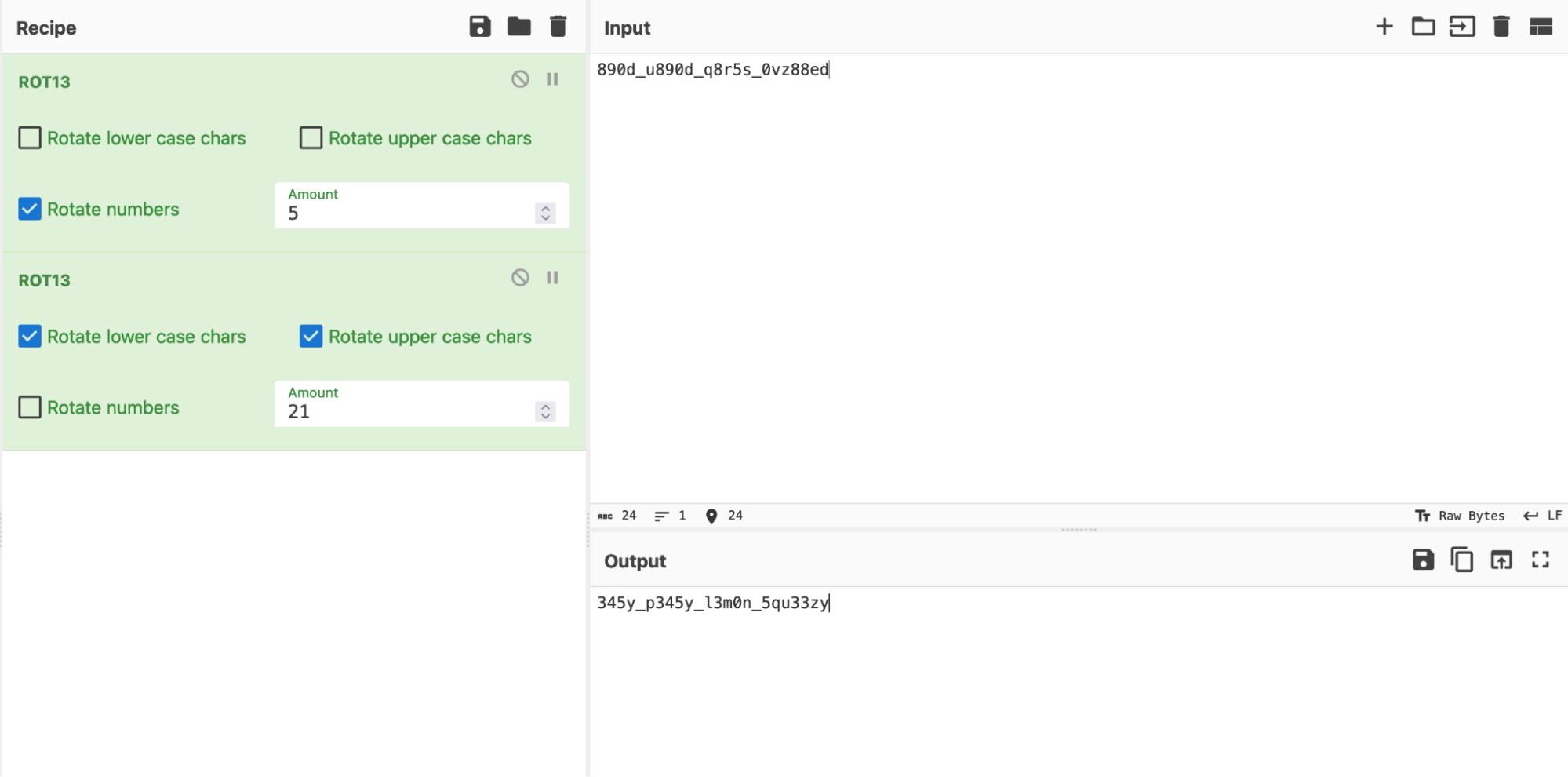

Let’s use CyberChef to apply the Caesar Cipher, using the new shift amounts. We will shift numbers first, then shift the alphabets next.

The flag is: CS2107{345y_p345y_l3m0n_5qu33zy}

M.1 AES ECB (20 marks)

I accidentally encrypted my file and forgot my password! Can you decrypt the file for me?

HINT: Flag is in printable ASCII format

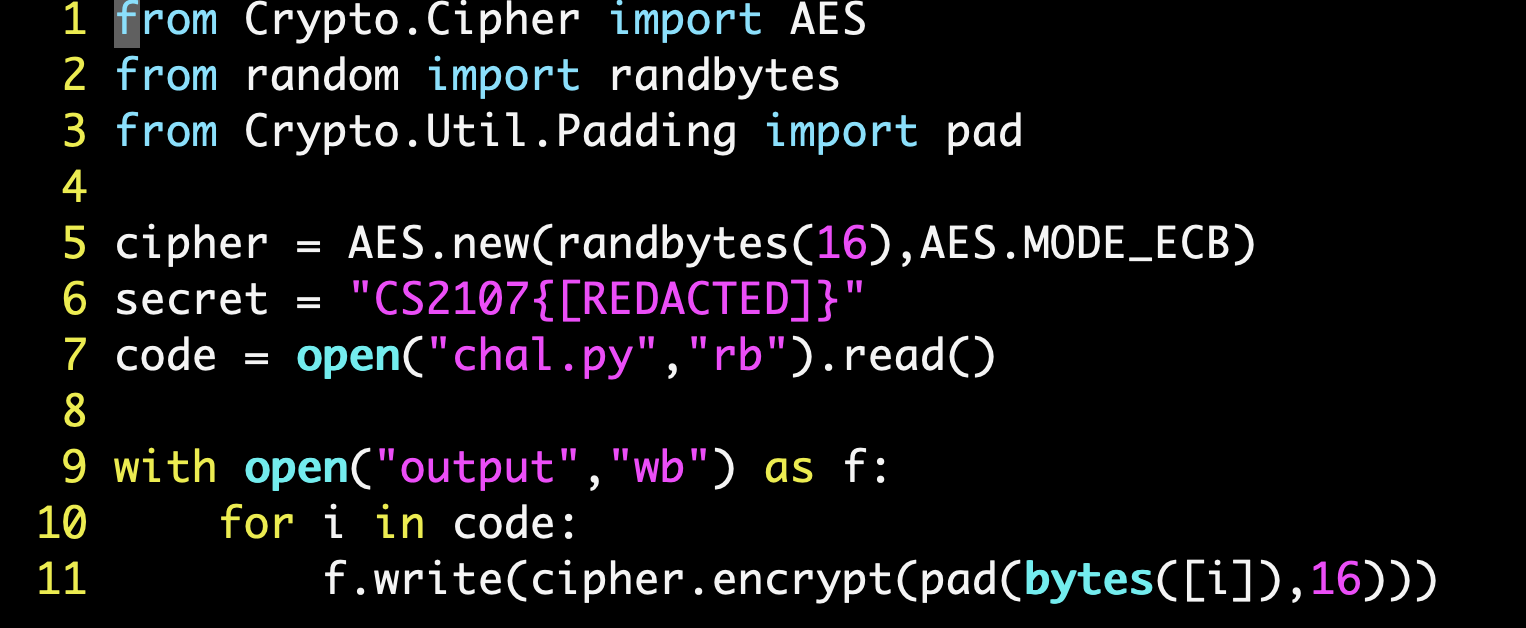

Let’s analyze the chal.py file that is provided to us.

We note the following:

- AES ECB mode was used for encryption using a random 16 byte key.

- AES ECB is deterministic!

-

The flag has been hard-coded into the Python script as a variable

secret - (Very Important!) The entire Python script was encrypted, byte by byte, to give the output. Each byte was padded such that it forms a block of 16 bytes in length.

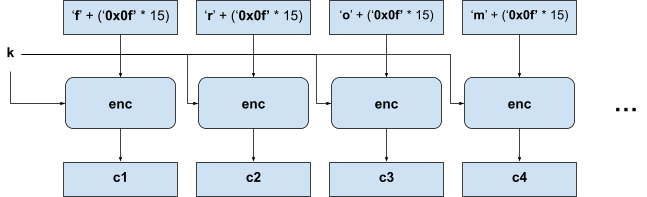

The encryption process might therefore look like this:

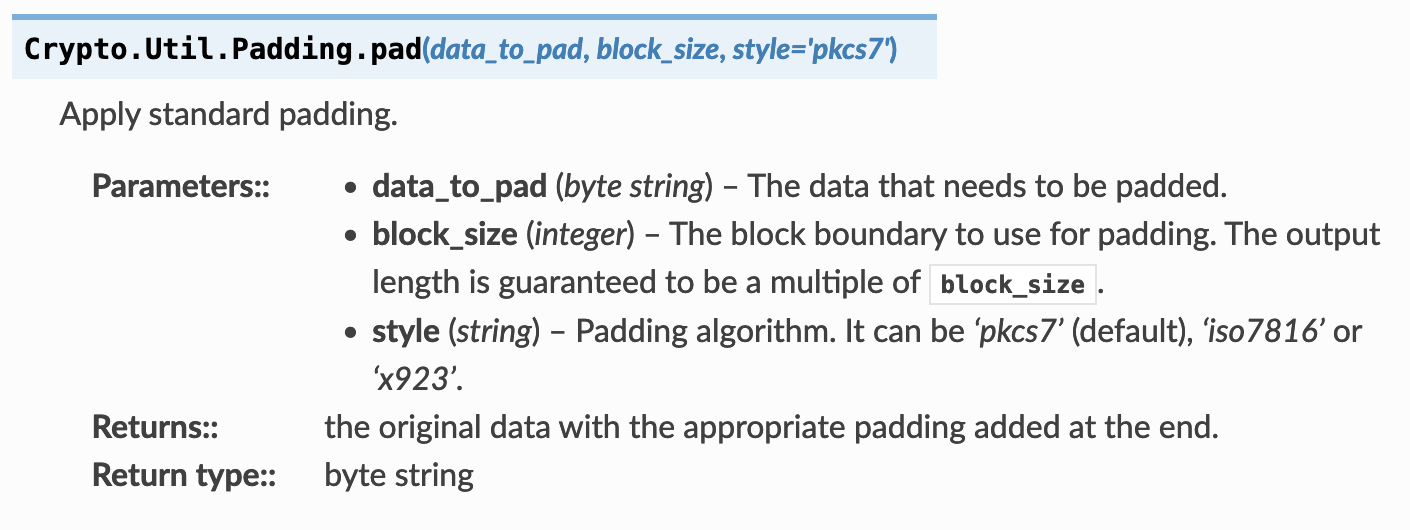

Essentially, each character in the script is extracted and padded using PKCS #7 standard (which is the default setting, since padding standard was not specified in line 11 of chal.py):

We conclude that each 16B block represents a character in the script. Given this information, we shall now attempt to determine the number of characters present in the flag.

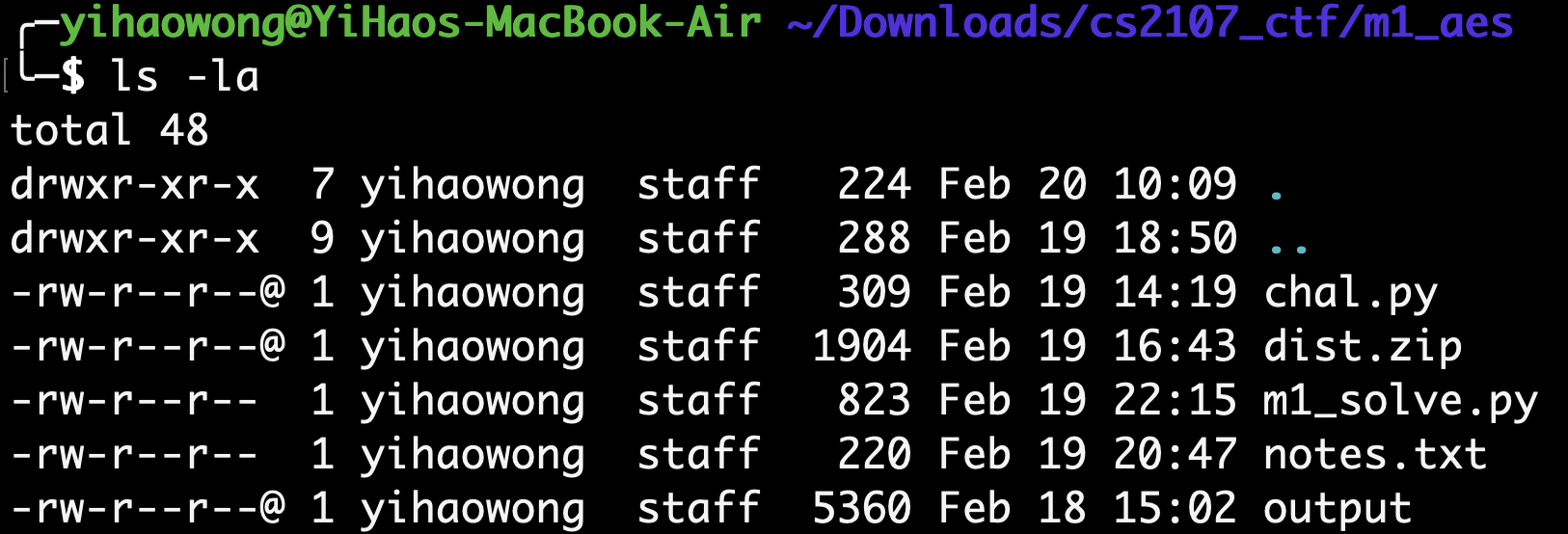

Using ls -la to view the file sizes (in bytes) of the chal.py file and the encrypted output:

We observe that the output is 5360B in size. Since we know that the output consists of a bunch of 16 byte blocks, we can determine the exact number of blocks present (and therefore, the number of characters) present in the original chal.py script.

- The number of characters present is $5360/16=335$

We also observe that the altered chal.py script has a size of 309B. Accounting for the dummy flag CS2107{[REDACTED]} placed in the file (which has a size of 18B, since each char is 1B), and assuming that the only difference between the original file and the altered file is the flag variable, we can then do some simple calculations to determine the size of the real flag.

- Real flag size is $335B-(309-18)B=44B$

Knowing this, let’s construct our solver Python script:

dummy_code = """from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from random import randbytes

from Crypto.Util.Padding import pad

cipher = AES.new(randbytes(16),AES.MODE_ECB)

secret = "CS2107{$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$}"

code = open("chal.py","rb").read()

with open("output","wb") as f:

for i in code:

f.write(cipher.encrypt(pad(bytes([i]),16)))

"""

with open('output', 'rb') as f:

fb = f.read()

block_char_map = {}

for i in range(0, len(fb), 16):

block = fb[i:i+16]

real_char = dummy_code[i//16]

if real_char == "$":

# Ignore filler char

continue

if block not in block_char_map:

block_char_map[block] = real_char

out = ""

for i in range(0, len(fb), 16):

out += block_char_map[fb[i:i+16]]

print(out)

Here, we essentially generate a dummy version of the chal.py code, where we replace the flag variable with a 44B long dummy flag made up of $ filler characters. Then, we simply iterate through each block in the output, and map each block to a plaintext character from the chal.py code (we ignore the filler characters in the flag). Lastly, we will decode the output using our block-to-char map.

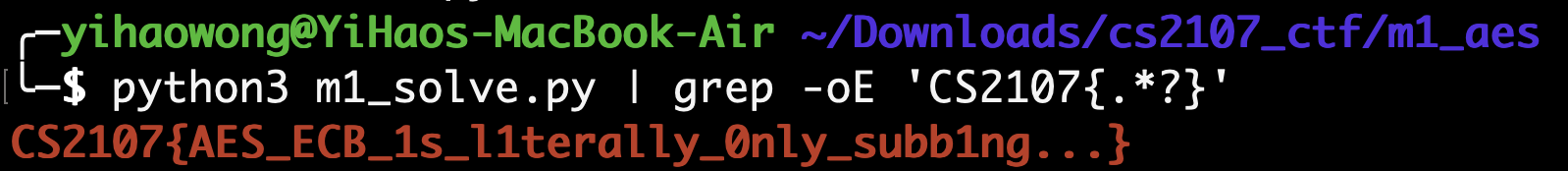

From the entire code block that is printed to standard output, simply grep the flag:

The flag is: CS2107{AES_ECB_1s_l1terally_0nly_subb1ng...}

M.2 baby shark (20 marks)

Baby Shark, doo-doo, doo-doo, doo-doo Baby Shark, doo-doo, doo-doo, doo-doo Baby Shark, doo-doo, doo-doo, doo-doo Baby Shark …

What files could be hidden within the pcapng file?

Flag Format:

CS2107{...}HINT: Wireshark could be useful in helping us to analyse pcapng files

HINT: Some HTTP file objects have been trasmitted, how can you extract those files?

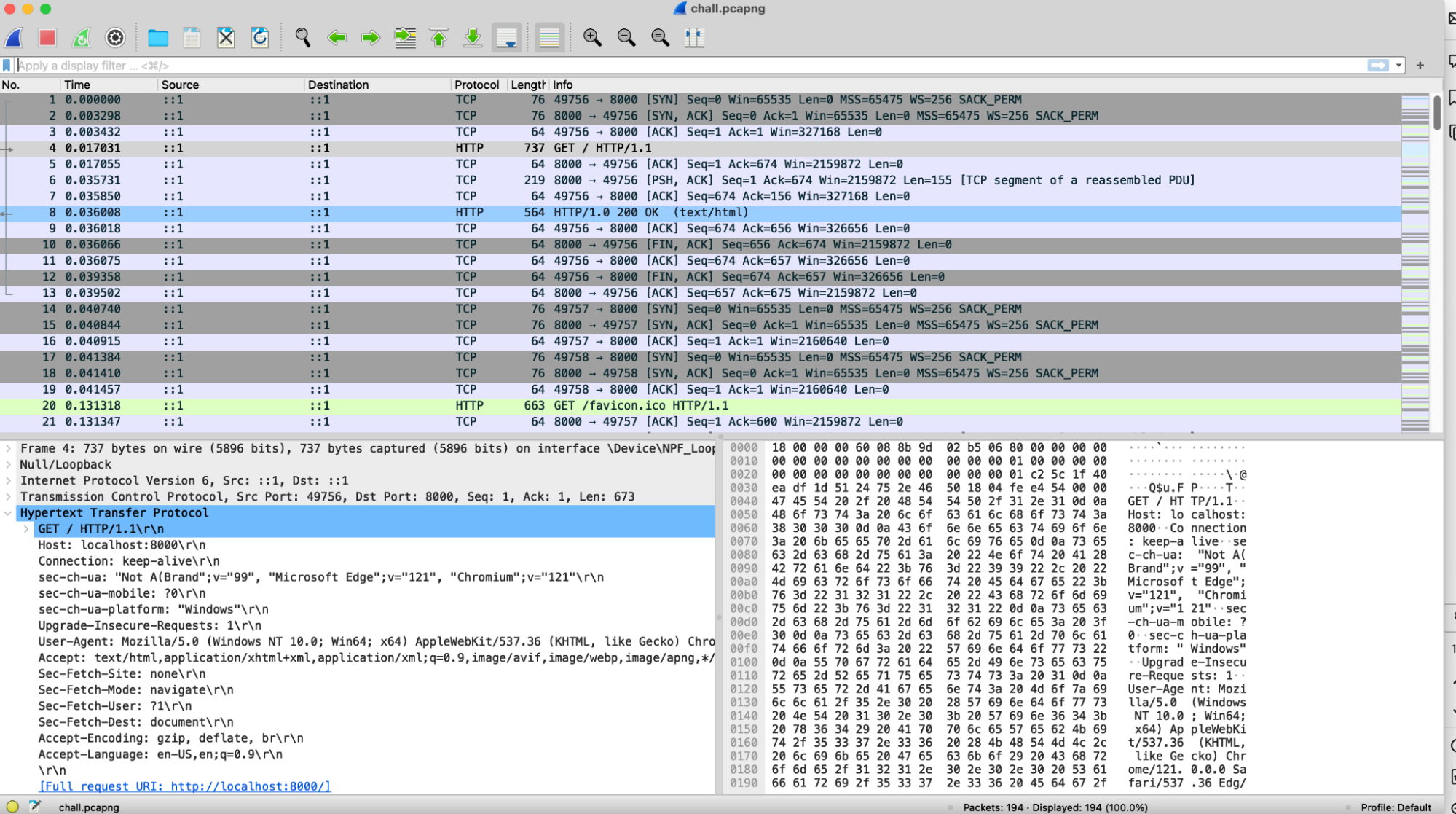

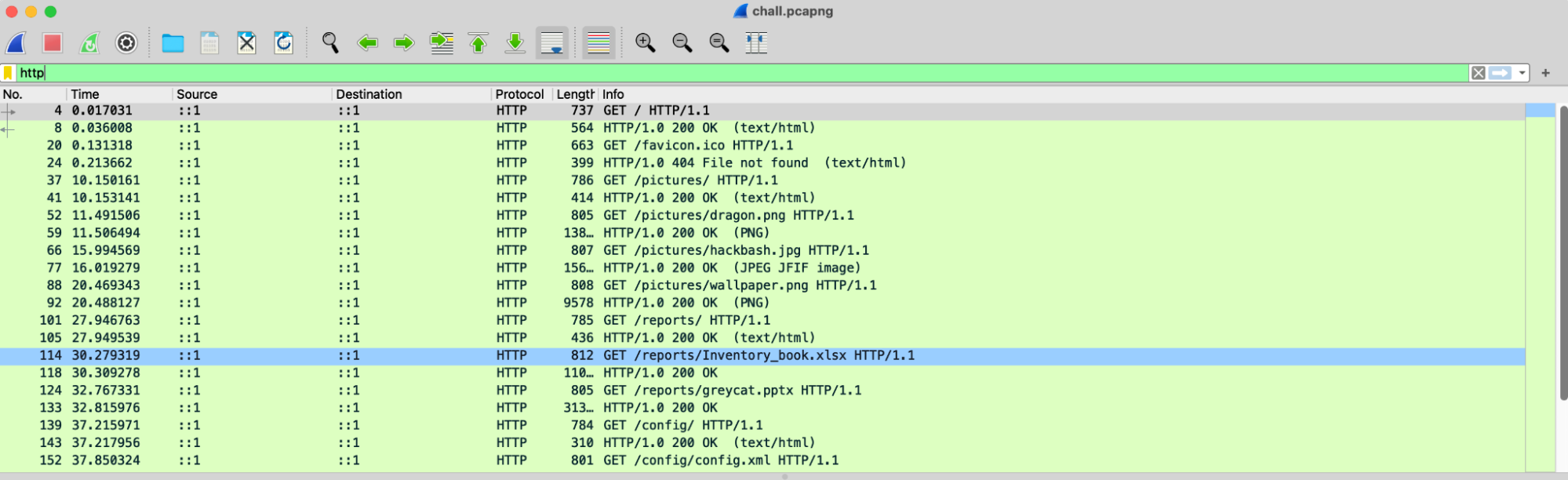

We will start off by analyzing the chall.pcapng file in Wireshark.

We mainly see a bunch of TCP and HTTP packets being captured. We can apply a filter to view just the HTTP packets transmitted.

Immediately, we see that files, such as .png and .xlsx files, have been transmitted between source and destination through HTTP GET requests.

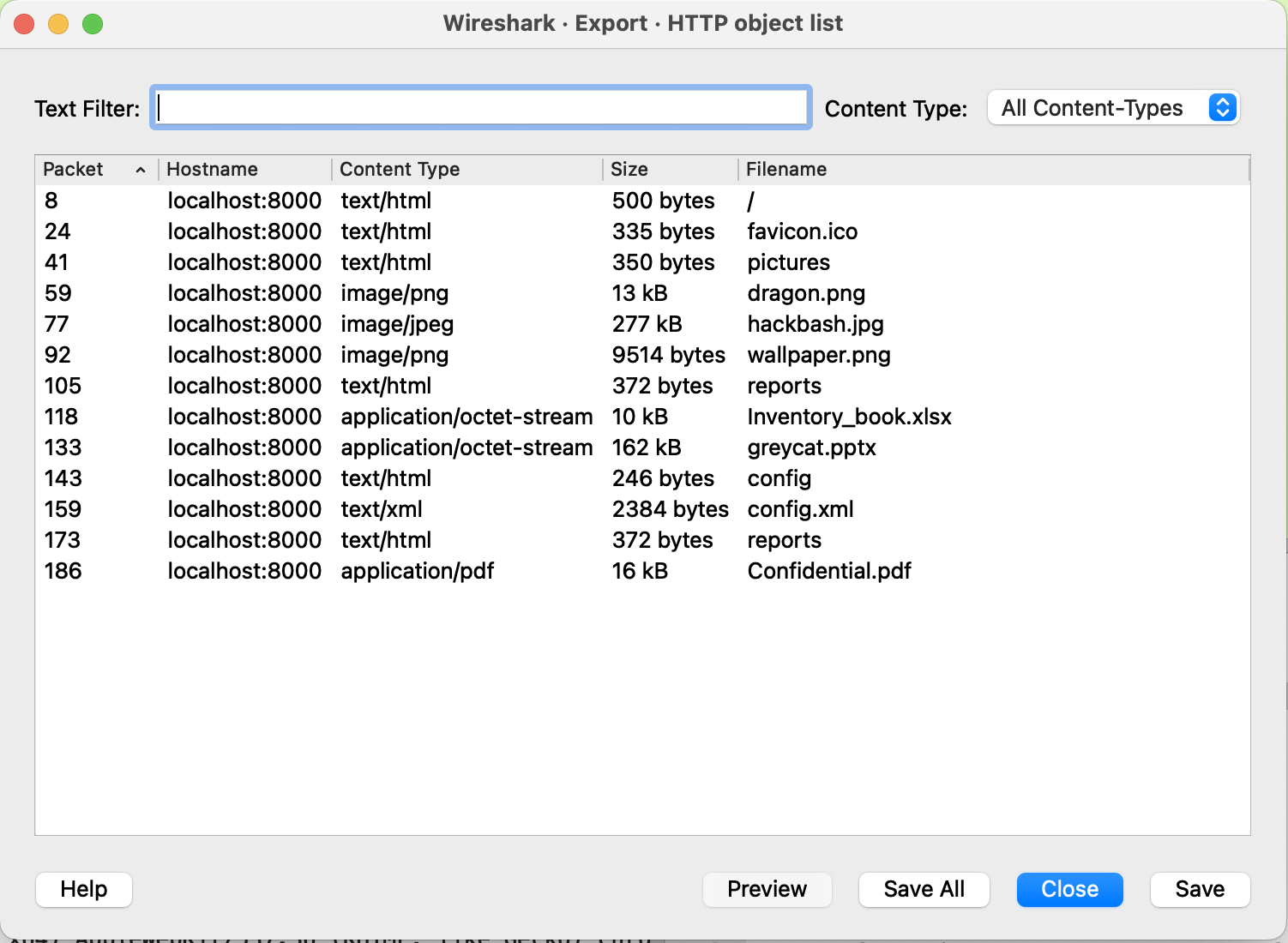

Let’s export these files to our local machine for analysis (File > Export Objects > HTTP):

From here, we just look through all these files to see if there is anything interesting in each file. Ideally, we’d like to find a part of the flag in each file.

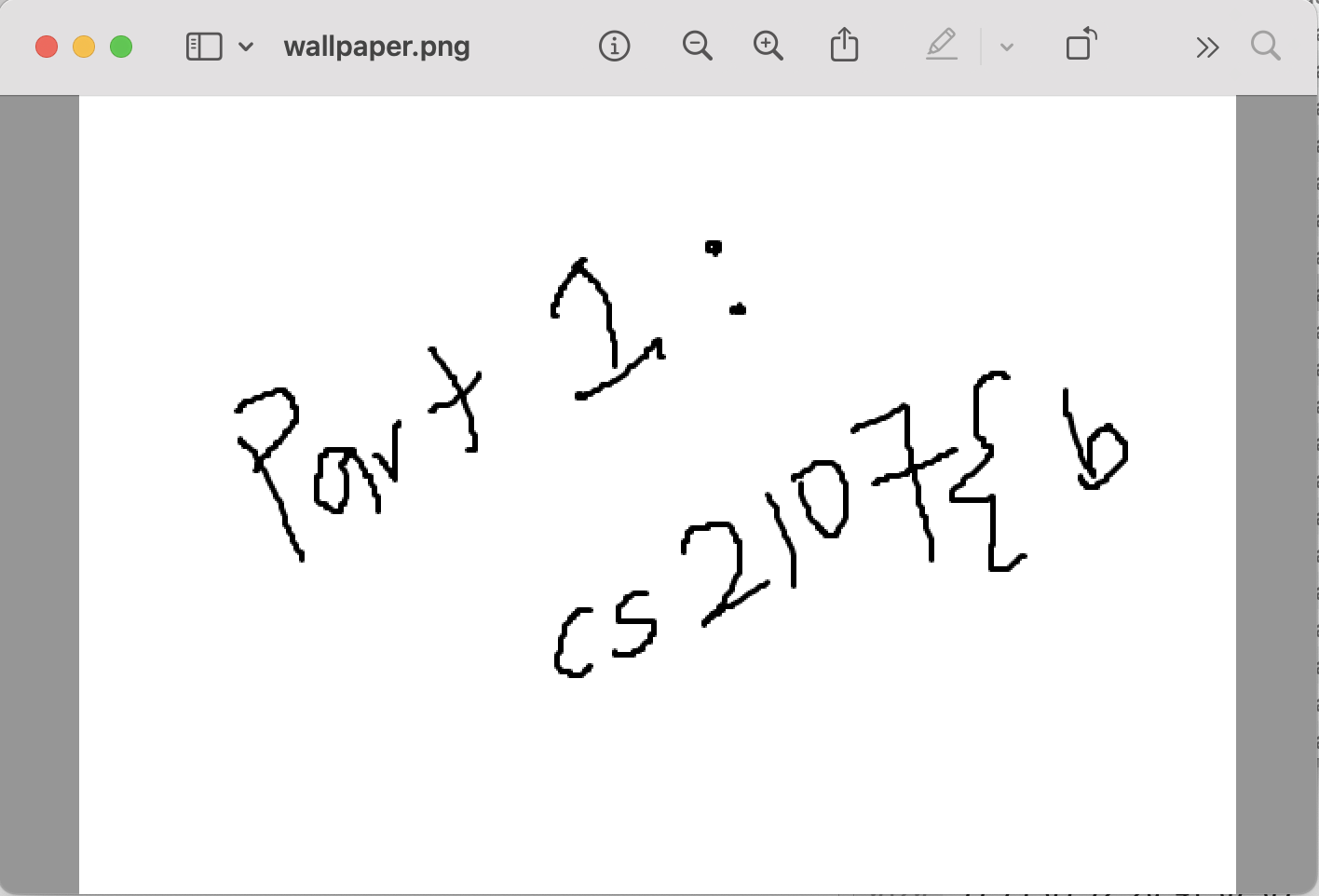

The first part of the flag can be found in wallpaper.png:

Part 1: CS2107{b

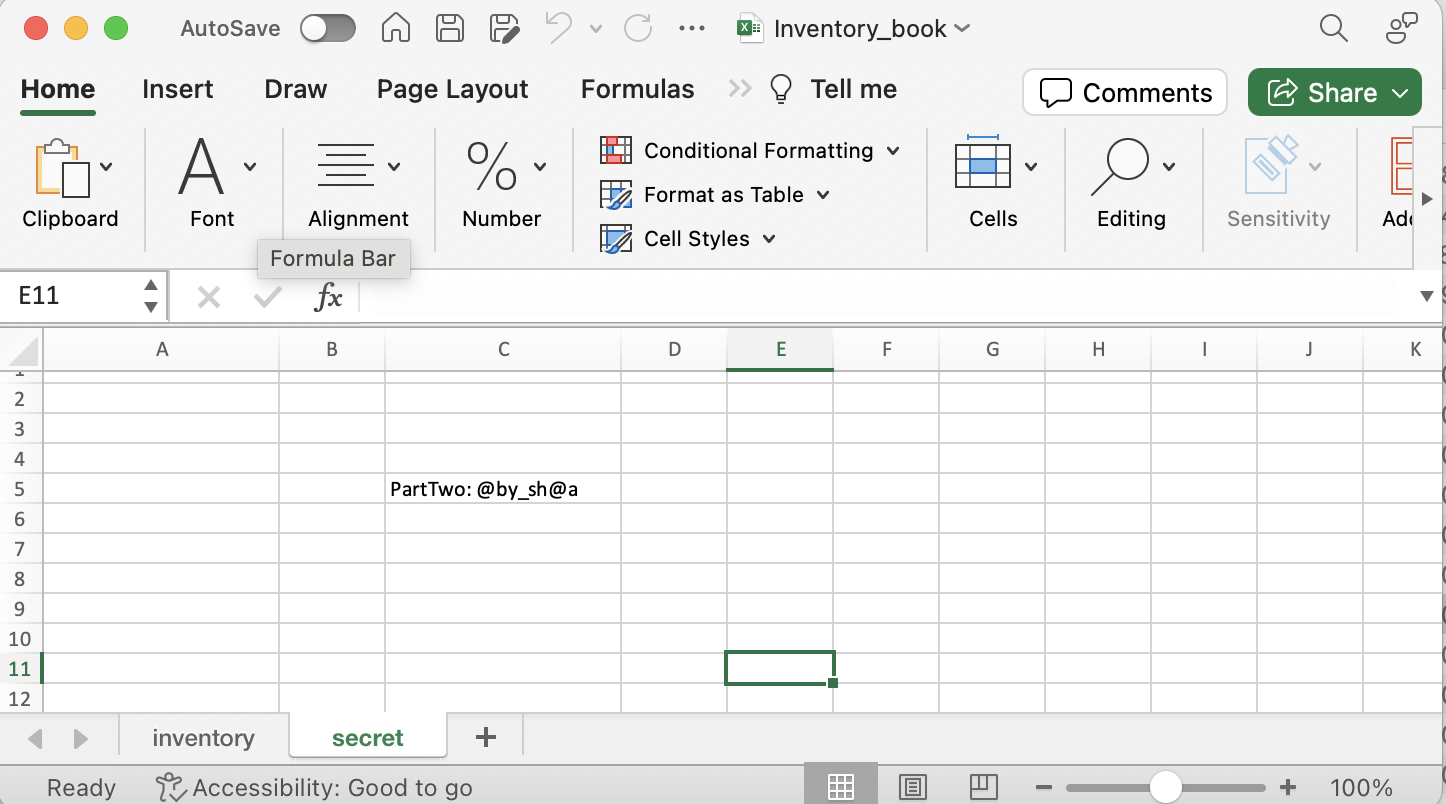

The second part of the flag can be found in Inventory_book.xlsx:

Part 2: @by_sh@a

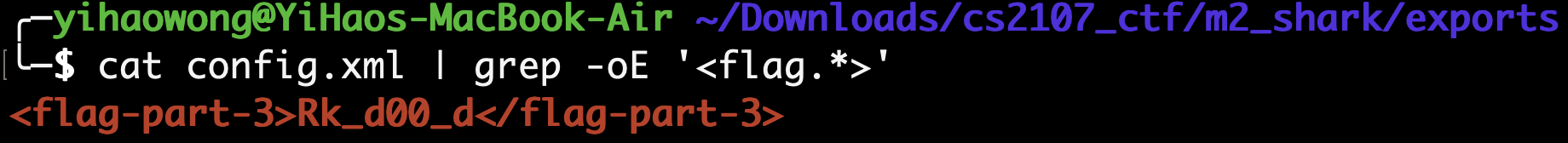

The third part of the flag can be found in config.xml:

Part 3: Rk_d00_d

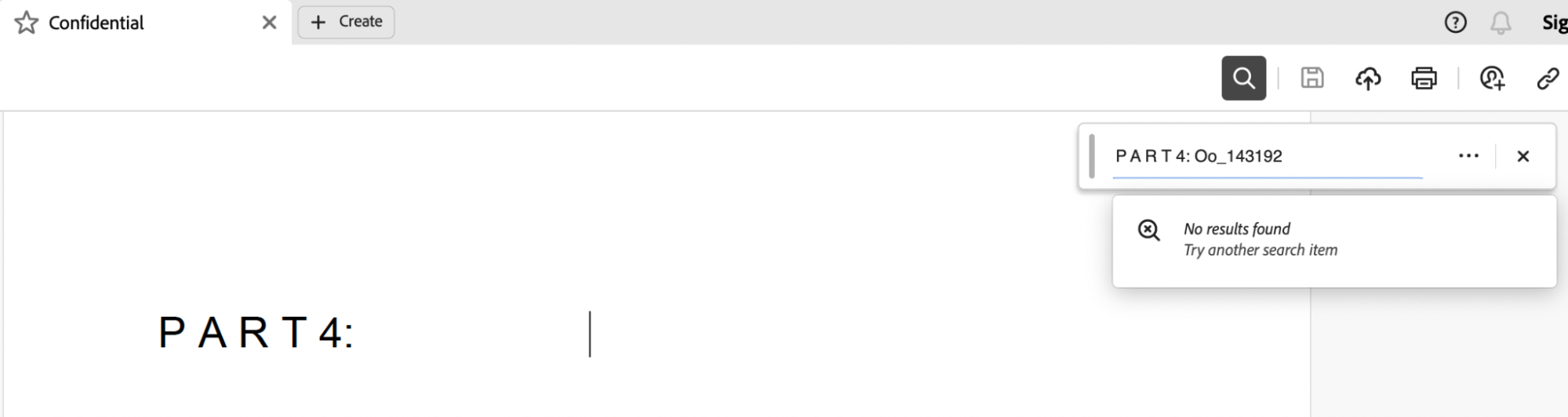

The last part of the flag can be found in Confidential.pdf, however, the flag text is hidden. To view the text, we just need to select and copy the hidden text, and paste it somewhere else for viewing (e.g., in the search bar):

Part 4: Oo_143192}

With this, just join all four parts of the flag together.

The flag is: CS2107{b@by_sh@aRk_d00_dOo_143192}

M.3 hash_key (20 marks)

Haiyaa! Why does everyone always insist on generating some random string for AES key? I prefer random numbers! To make this even more secure than the silly random string, I even hash the number into a super long string that you can’t possibly guess.

I have encrypted a secret message using this technique. The encryption source code, as well as the output of the encryption, are given.

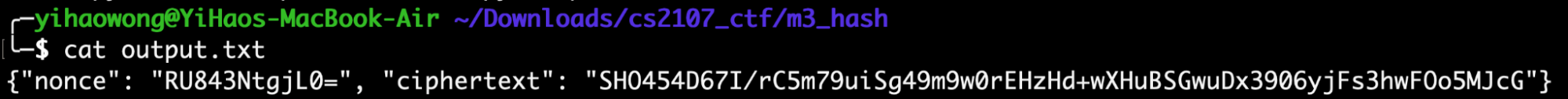

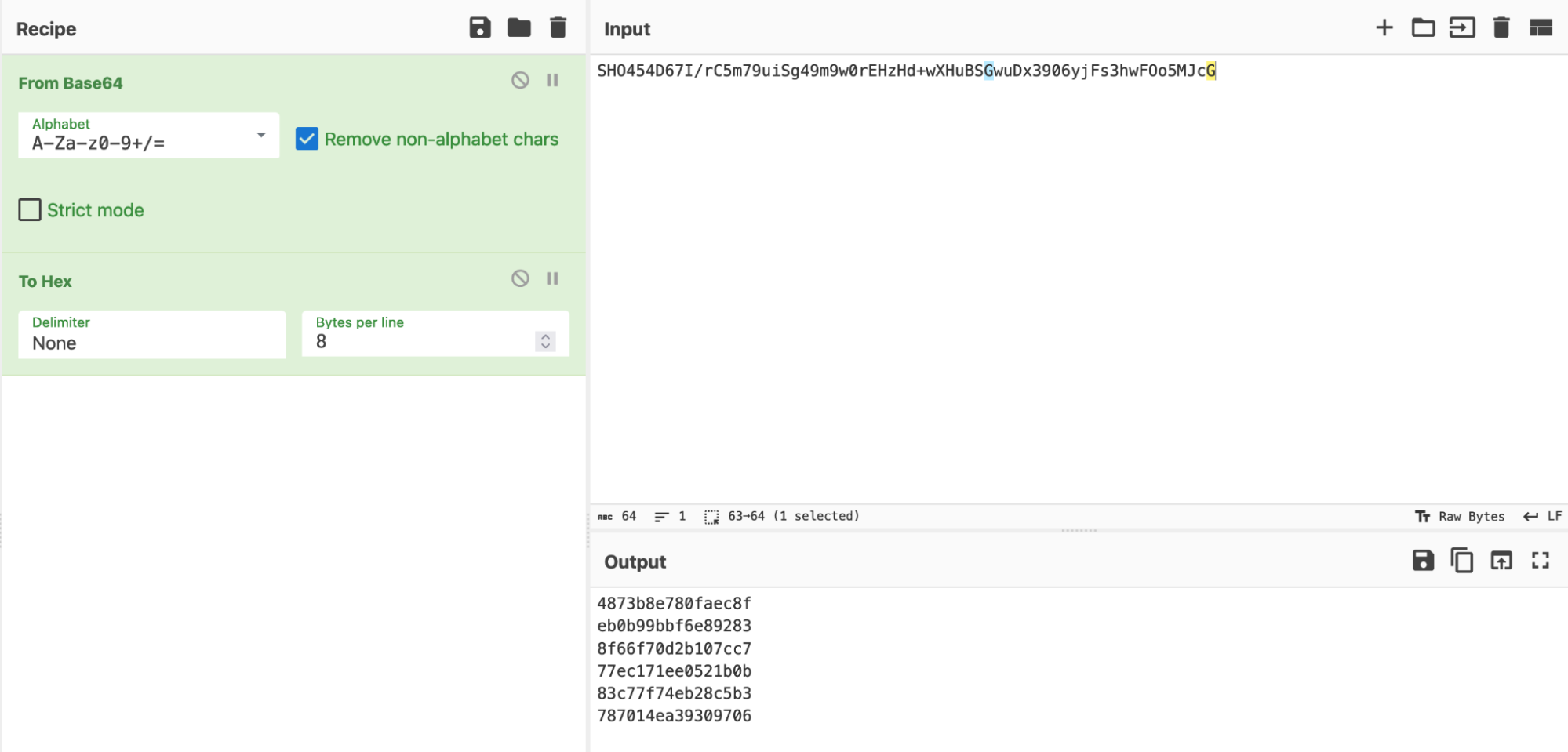

If we view the content of output.txt, we will see a nonce (IV) and ciphertext (both encoded in base-64).

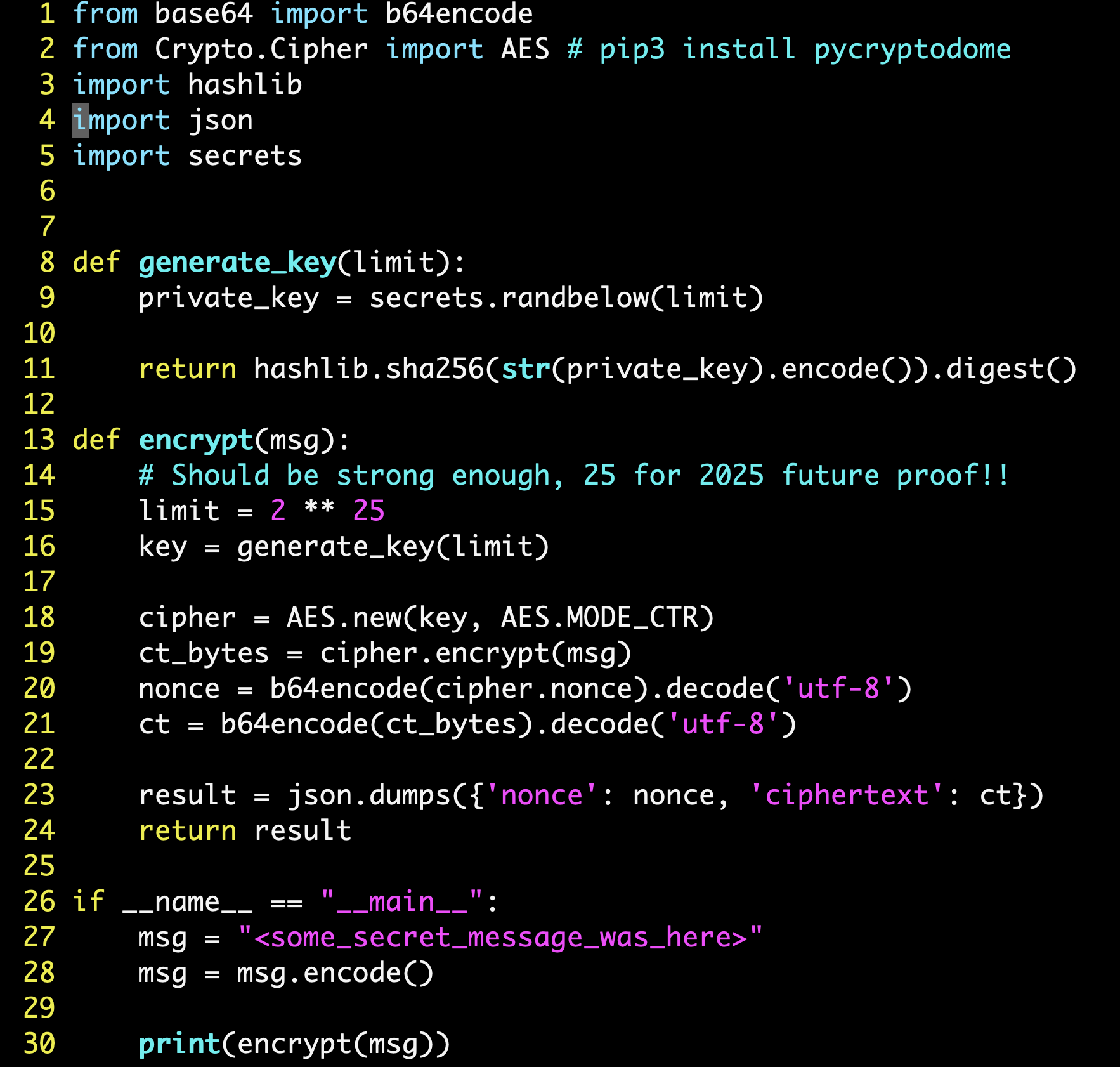

We know that AES encryption was used. To determine the mode of operation, let’s look at chall.py.

From this, we can note down a few things:

-

AES CTR mode was used for encryption.

-

The keyspace has a size of $2^{25}$- this is easily brute-forceable!

- This is because of the key generation algorithm used - a random number between 0 to $2^{25}$ was chosen, and that number is passed into SHA-256 to generate a hash digest (which is used as the AES key).

Given that the key can be brute-forced due to the small keyspace, we will attempt to break the encryption through an exhaustive search.

Another important thing to note here, is that AES CTR mode was used. AES CTR mode is vulnerable if we reuse a key and nonce for encryption, as this results in the same pseudorandom sequence (keystream) being generated by the AES algorithm. We will thus reuse the same nonce (provided in output.txt) in our exhaustive search.

Crucially, we are assuming that only the flag (in the CS2107{xxx} format) was encrypted. We’ll now need to derive the flag size (in bytes). For this, I’m assuming that the ciphertext and plaintext have the same size.

From the ciphertext provided, we can decode it into hex using CyberChef.

We therefore note that the flag size is 48B.

Now, let’s solve this using Python.

from base64 import b64decode

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

import hashlib

import json

flag = ("CS2107{" + ("A"*40) + "}").encode()

def generate_key(val):

return hashlib.sha256(str(val).encode()).digest()

def encrypt(key, nonce, msg):

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CTR, nonce=nonce)

ct_bytes = cipher.encrypt(msg)

return ct_bytes

def decrypt(key, nonce, ct):

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CTR, nonce=nonce)

pt_bytes = cipher.decrypt(ct)

return pt_bytes

with open('output.txt', 'r') as f:

input_json = f.read()

b64 = json.loads(input_json)

nonce = b64decode(b64['nonce'])

ct = b64decode(b64['ciphertext'])

key = 0

for i in range(2**25):

cur_key = generate_key(i)

ct_bytes = encrypt(cur_key, nonce, flag)

if ct_bytes[:6] == ct[:6]:

print("key value is:", i)

key = i

break

pt = decrypt(generate_key(key), nonce, ct).decode()

print(pt)

Firstly, we want to craft a dummy flag of 48B in length. However, note that in our exhaustive search, we are only interested in the first 6 characters (CS2107) of the flag.

For each possible key value, try to encrypt our dummy flag. If the key value is correct, our encrypted flag will be highly similar to the ciphertext provided.

To elaborate:

-

Let $r$ represent the keystream (derived from the key-nonce pair). Suppose that, in the original encryption, the first 6B of the ciphertext is the result of $``CS2107”_{original} \oplus r$.

-

If we arrive at the correct key-nonce pair during our exhaustive search, we will get the exact same keystream $r$.

-

Then, encrypting the first 6 bytes of our dummy flag will also yield the same result. That is, $

CS2107"_{original} \oplus r=CS2107”_{dummy} \oplus r$. -

Therefore, we know that we have derived the correct key value.

Running the script, we derive that the integer value 15230891 was used to create the AES key.

Then, simply decrypt the ciphertext using the key value derived.

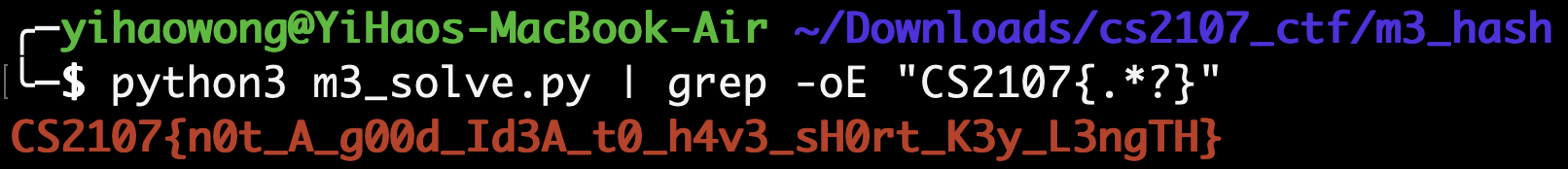

The flag is: CS2107{n0t_A_g00d_Id3A_t0_h4v3_sH0rt_K3y_L3ngTH}

M.4 Salad (20 marks)

We have intercepted an encrypted text file from a malicious hacker group, and we also managed to retrieve this weird python file that we think might have something to do with it, can you help us crack this encrypted message?

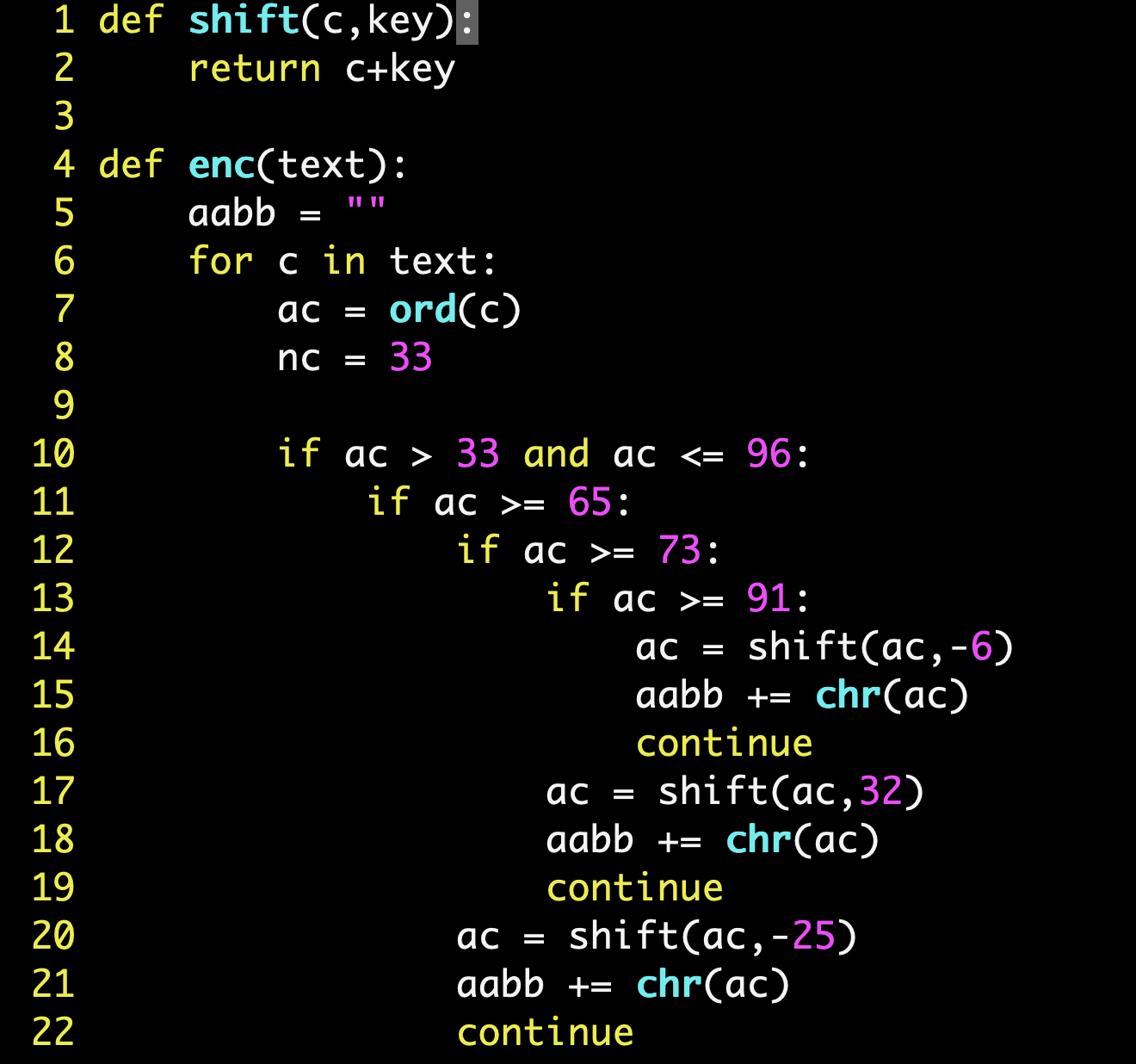

Let’s open salad.py.

Right off the bat, we are greeted with a piece of obfuscated code.

Let’s attempt to deobfuscate the code.

Reading through the code, we can easily notice that for each character in the flag, the ASCII value of the character is retrieved. Then, depending on the ASCII value, a shift amount is applied, and the resultant ASCII character is appended to the output (salad.txt).

We can summarize the respective shift amounts in the following table:

| Original ASCII code range | Shift Amount | New ASCII code range |

|---|---|---|

| 117-122 | -83 | 34-39 |

| 123-125 | -68 | 55-57 |

| 34-47 | 57 | 91-104 |

| 48-54 | 10 | 58-64 |

| 55-57 | 68 | 123-125 |

| 58-64 | -10 | 48-54 |

| 65-72 | -25 | 40-47 |

| 73-90 | 32 | 105-122 |

| 91-96 | -6 | 85-90 |

| 97-116 | -32 | 65-84 |

Also, if the ASCII character encountered is ! (ASCII code of 33), it is substituted with ~ (ASCII code of 126).

To solve this, simply reverse the shift process. For each character in salad.txt, depending on the range of ASCII values in which it falls, we add/subtract the respective shift amounts accordingly to derive the original ASCII character.

We can solve this using a Python script:

def shift(c,key):

return c+key

def decrypt(text):

output = ""

for c in text:

ascii_code = ord(c)

nc = 33

if ascii_code >= 34 and ascii_code <= 39:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, 83))

continue

if ascii_code >= 40 and ascii_code <= 47:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, 25))

continue

if ascii_code >= 48 and ascii_code <= 54:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, 10))

continue

if ascii_code >= 55 and ascii_code <= 57:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, 68))

continue

if ascii_code >= 58 and ascii_code <= 64:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, -10))

continue

if ascii_code >= 65 and ascii_code <= 84:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, 32))

continue

if ascii_code >= 85 and ascii_code <= 90:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, 6))

continue

if ascii_code >= 91 and ascii_code <= 104:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, -57))

continue

if ascii_code >= 105 and ascii_code <= 122:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, -32))

continue

if ascii_code >= 123 and ascii_code <= 125:

output += chr(shift(ascii_code, -68))

continue

if ascii_code == 126:

nc = 33

output += chr(nc)

return output

if __name__ == "__main__":

enc_txt = open("salad.txt", "r").readline().strip()

print(decrypt(enc_txt))

The flag is: CS2107{m45t3r_0f_sub5ti7u7i0n_3nj0y_uR_s4l@d!!}

H.1 Broadcasting (20 marks)

I have a really cool message that I want to share to all my friends. To ensure that no sneaky people obtain this message, I will use RSA encryption. For extra safety, I will generate a different RSA key pair for each friend of mine.

Surely this is safe! I have provided the source code and the output that I sent to my friends.

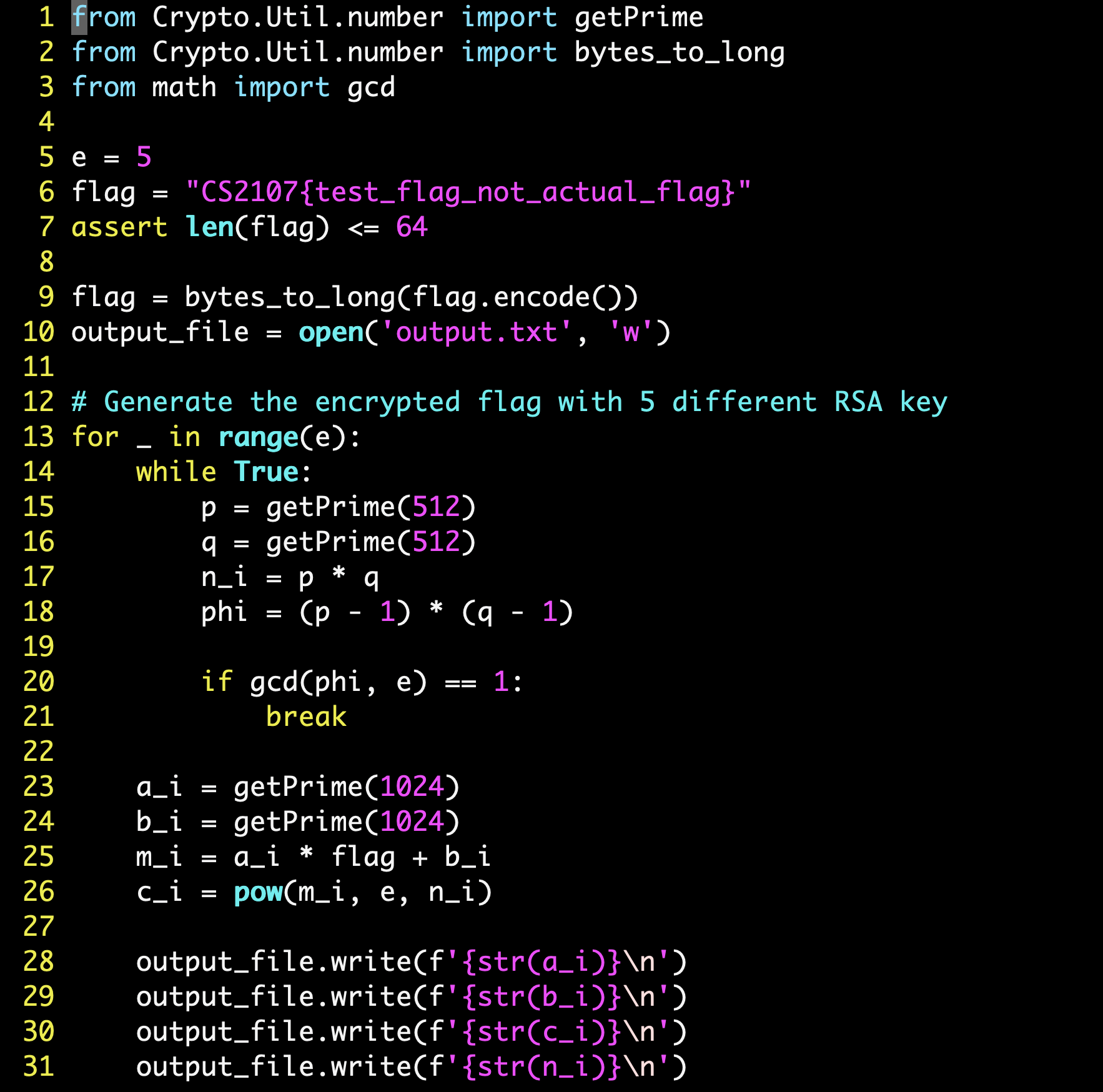

Viewing output.txt does not give us any immediately meaningful information. To figure out what the lines in output.txt represent, we have to look at chall.py.

Looking through chall.py, we note down a few crucial things:

-

Flag length is no longer than 64B in size (relatively small message).

-

Exponent is very small ($e=5$).

-

RSA is being used to encrypt the flag 5 times. For each encryption, random valid $p$ and $q$ values are being generated to compute $n$.

-

Importantly, the flag text is being padded with random values of $a$ and $b$.

We also now know that every 4 lines of output.txt contain a key for a recipient (let’s consider a set of $a$, $b$, $c$ and $n$ values as a key).

We can thus generalize the encryption process as such: $c_i=(m_i)^5 \mod n_i , \forall i \in [1,5]$, where each $m_i=(a_i \times flag)+b_i$

Since $n$ was provided, I attempted to try and find its factors ($p$ and $q$) using FactorDB. However, this didn’t work as $n$ was too large. I thus decided to look for another approach.

After a Google search, I found out that a form of attack which could be employed, would be a Hastad’s Broadcast Attack. Crucially, the attack works here because the number of ciphertexts $k$ is the same as the exponent $e$. That is, the $k \geq e$ condition is satisfied, since $k=5$ and $e=5$.

The standard attack utilizes the Chinese Remainder Theorem to derive a unique value for $m$. Suppose that all $n$ are relatively prime (that is, $gcd(n_i, n_j)=1, \forall i,j$), and $e=5$. Then, we can derive the unique value of $m^5$ (and therefore, $m$, by taking the 5th root of $m^5$) from the following encryptions:

$m^5=c_1 \mod n_1$ $m^5=c_2 \mod n_2$ $…$ $m^5=c_5 \mod n_5$

(I’ve omitted details on how to solve this system using CRT for the sake of brevity.)

Crucially, we must note that the normal attack does not work here, as $m$ is slightly different for each encryption (due to the linear padding applied). However, Hastad has also proved that the attack can be generalized to account for a linear padding on the message, though the approach to solve this is slightly different from the one mentioned earlier.

I will attempt to simplify the proof given in the Wikipedia page: Coppersmith’s attack (Hastad’s Broadcast Attack), and also provide the details of the algorithm: (P.S. My math background is not that strong, so there are still some parts of this proof which I don’t understand.)

-

Since all $n$ are relatively prime, we will compute $T_i$ such that for all $i \leq e$, $T_i=1 \mod n_i$, and $T_i=0 \mod n_j$, $\forall i \neq j$

This can be computed using the Chinese Remainder Theorem. For example, when $i=1$ and $e=5$, we want to derive the unique value of $T_1$ from the following system of congruences: $T_1=1 \mod n_1$ $T_1=0 \mod n_2$ $T_1=0 \mod n_3$ $T_1=0 \mod n_4$ $T_1=0 \mod n_5$

-

Now, we will compute our combined polynomial $g(x)$ as follows: $g(x)= \sum_{i=1}^5T_i \cdot f_i(x)$, where each $f_i(x)=(a_i \times x)+b_i$

Crucially, in this stage, we note that this property holds true for all values of $i$: $g(m)=0 \mod n_i$.

Therefore, $g(m)=0 \mod N$, where $N=\prod_{i=1}^5n_i$.

-

Recall that we found out earlier that the flag length is relatively small. We can thus assume that $m<n_i$ , where m represents our flag value.

Because of this, we can conclude that $m^5<N$, and $m<N^{1/5}$. We can use Coppersmith’s method to derive all integer roots of the monic polynomial $g(x) \mod N$, and we know that our flag value $m$ will be one of the roots of this polynomial.

We will solve this challenge using SageMath.

from binascii import unhexlify

data = open('output.txt', 'r')

tokens = data.read().split()

a_list = []

b_list = []

c_list = []

n_list = []

for i in range(0, len(tokens), 4):

a_list.append(Integer(tokens[i].strip()))

b_list.append(Integer(tokens[i+1].strip()))

c_list.append(Integer(tokens[i+2].strip()))

n_list.append(Integer(tokens[i+3].strip()))

T_list = []

for i in range(5):

# Determine unique value of Ti for system of congruences Ti = x mod nj

# Use a matrix to represent all x values

x_list = []

for j in range(5):

if i == j:

x_list.append(1)

else:

x_list.append(0)

T_list.append(crt(x_list, n_list))

# Generate monic g(x) to be solved using Coppersmith's theorem

N = 1

for i in range(5):

N *= n_list[i]

P.<x> = PolynomialRing(Zmod(N))

gx = 0

for i in range(5):

gx += T_list[i] * ((a_list[i] * x + b_list[i]) ** 5 - c_list[i])

gx = gx.monic()

roots = gx.small_roots()

# Get flag

flag = unhexlify(hex(int(roots[0]))[2:]).decode()

print(flag)

The flag is: CS2107{s0c3R3r_0f_H4sTAD_Br0ADC4sT_aTT4ck!!!}

H.2 Secure Password (20 marks)

I forgot my password and lost access to my secret vault :( Luckily I downloaded a copy of the website. Could you help me recover the password?

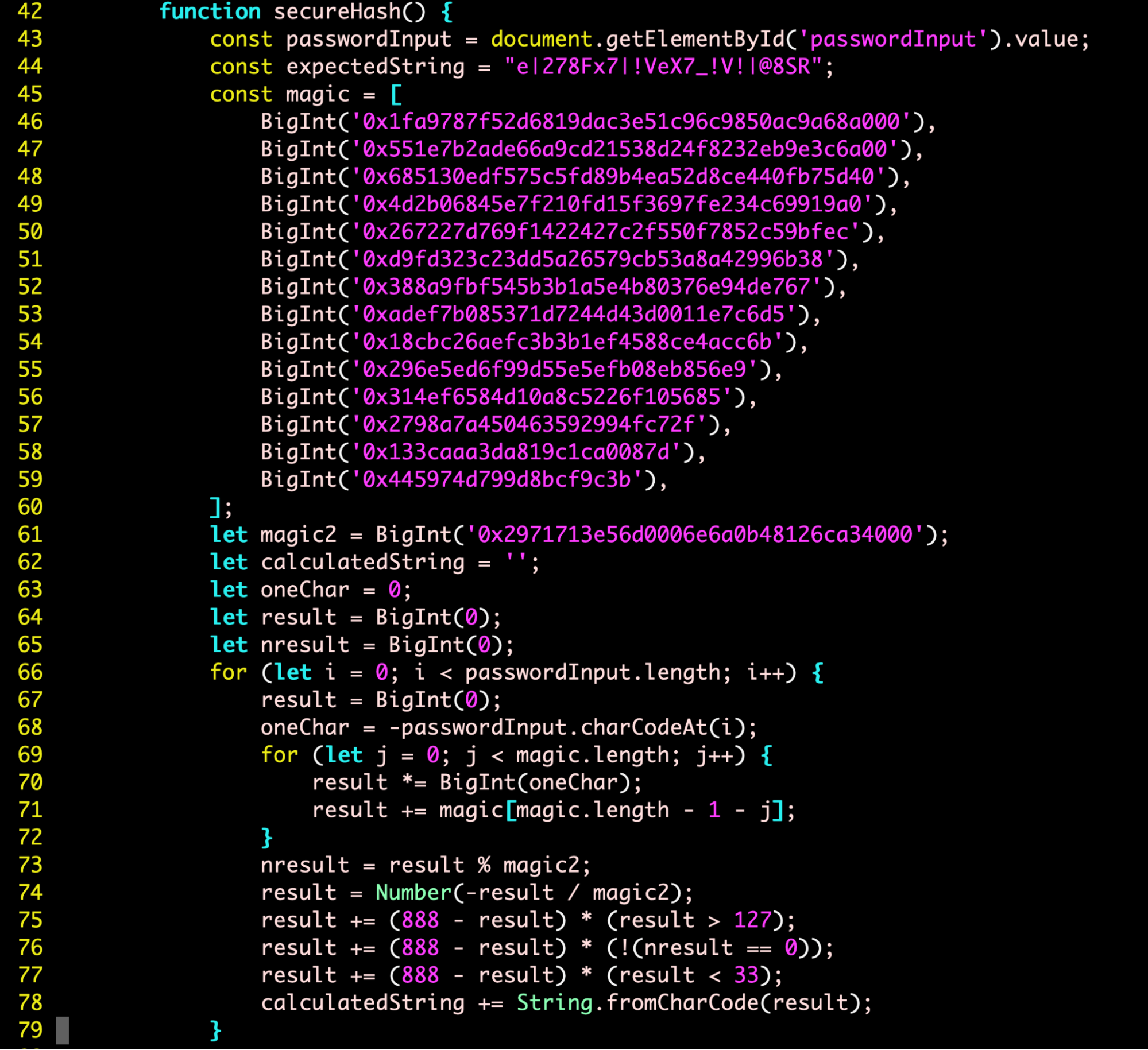

We will start off by looking at the chal.html file that is provided to us. Interestingly, there is a piece of JavaScript code embedded within the HTML file (to validate the input provided by the user on the webpage):

From this secureHash() function, we notice two things:

-

The hash function hashes the user input, and validates it by comparing it to the

expectedString. -

Each character of the input is individually hashed, and appended to the

calculatedStringvariable. If the user input is valid,calculatedStringwill be equivalent toexpectedString.

Firstly, I try to determine what the expected size and format of the input string should be. It is easy to determine the expected size of the input, since the input should be of the same length as the expectedString variable. Thus, the expected size of the input is 23B.

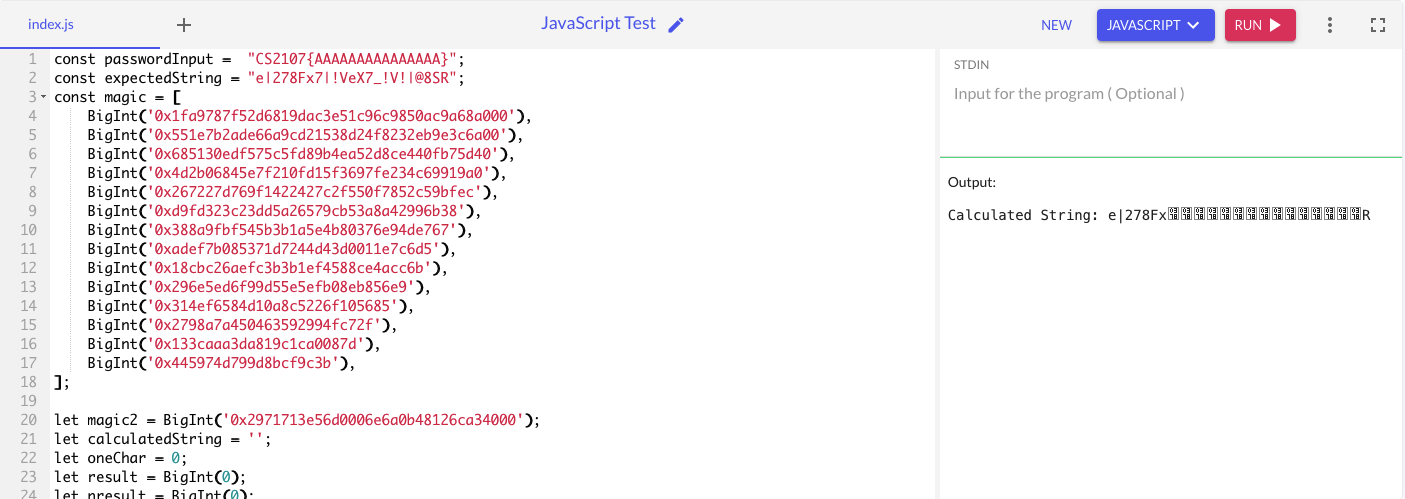

Regarding the format of the input string, I assumed that the expected input would be a flag in the CS2107{xxx} format. To test this, I plugged in a 23B dummy flag into this hashing function, and checked the output.

Indeed, the expected input is a flag. We can see that the CS2107{ and } portions of the flag are hashed correctly, and match the relevant portions of our expected string.

We can easily solve this challenge by using a hash-to-character map, where we map all possible ASCII characters to their hash (generated by the provided function). Then, just iterate over the expected string to derive its corresponding input character (preimage) from the hash-to-character map.

I’ll use a Python script to solve this challenge (I converted the JavaScript code into its Python equivalent):

expectedString = "e|278Fx7|!VeX7_!V!|@8SR"

magic = [

int('0x1fa9787f52d6819dac3e51c96c9850ac9a68a000', 16),

int('0x551e7b2ade66a9cd21538d24f8232eb9e3c6a00', 16),

int('0x685130edf575c5fd89b4ea52d8ce440fb75d40', 16),

int('0x4d2b06845e7f210fd15f3697fe234c69919a0', 16),

int('0x267227d769f1422427c2f550f7852c59bfec', 16),

int('0xd9fd323c23dd5a26579cb53a8a42996b38', 16),

int('0x388a9fbf545b3b1a5e4b80376e94de767', 16),

int('0xadef7b085371d7244d43d0011e7c6d5', 16),

int('0x18cbc26aefc3b3b1ef4588ce4acc6b', 16),

int('0x296e5ed6f99d55e5efb08eb856e9', 16),

int('0x314ef6584d10a8c5226f105685', 16),

int('0x2798a7a450463592994fc72f', 16),

int('0x133caaa3da819c1ca0087d', 16),

int('0x445974d799d8bcf9c3b', 16),

]

magic2 = int('0x2971713e56d0006e6a0b48126ca34000', 16)

calculatedString = ''

oneChar = 0

result = int(0)

nresult = int(0)

hash_char_map = {}

def generate(char):

result = int(0)

oneChar = -(ord(char))

for j in range(len(magic)):

result *= int(oneChar)

result += magic[len(magic) - 1 - j]

nresult = result % magic2

result = float(-result / magic2);

result += (888 - result) * (result > 127)

result += (888 - result) * (not (nresult == 0))

result += (888 - result) * (result < 33)

return chr(int(result))

for i in range(256):

result = generate(chr(i))

hash_char_map[result] = chr(i)

output = ""

for i in expectedString:

output += hash_char_map[i]

print(output)

The flag is: CS2107{1S_4Ct1y_4_Sb0x}